Maybe the most vivid and immediate appeal of fantasy fiction is that of visiting another world. The other enticements—exploring the human condition, reading about some neat swordfights—come later. Like a lot of SFF writers, I got my start writing a series of travel guides to imaginary kingdoms, with narrative and character turning up later.

But I’ve always really loved fantasy worlds where there isn’t just one imaginary place, either existing by itself or connected to our own working-day world, but a whole nexus of interconnected universes. In space opera, for instance, the idea of visiting other worlds is commonplace—but here I’m not talking about visiting many other planets but many other realities. Philip Pullman’s His Dark Materials books were my introduction to this kind of multiverse, but they surely need no introduction! In this kind of setting, every world has its own rules to learn and its own dangers to face. There is a sense of infinite possibility and variety, with just a hint at the cliff-edge terror of immensity, the ever-present risk that you might get lost far from home.

The Lives of Christopher Chant by Diana Wynne Jones

The portal fantasy is a staple of children’s literature in particular: the idea that some secret world exists beyond reality is appealing in the same way as the idea of making a secret den or fort to be your refuge from the demands of the real world. The genius of The Lives of Christopher Chant is that Christopher travels between worlds the same way anyone might: by visualising the path to the Place Between as he’s about to fall asleep, and imagining his way into other realities. It’s utterly plausible both as a means of interdimensional travel and as part of the inner world of a neglected child who has to keep himself company a lot of the time.

Diana Wynne Jones returned to this setting many times in a whole series of loosely-connected novels; often it’s largely an excuse for adding a few familiar characters to a new setting. For my money this is the best book she ever wrote, and it’s also the one in which she makes the most of the eldritch geography of the Place Between and the many worlds beyond it. It works so well in part as a mirror to Christopher’s own emergence from isolation—this is a book about an interdimensional criminal gang, a mystery in which the clues are expertly seeded, but it’s also about an unhappy boy forging his own happiness out of years of loneliness.

The Magician’s Nephew by C.S. Lewis

The Narnia books, particularly The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, are perhaps the archetypal portal fantasy, in which children from our world find their way to a fantasy kingdom through a mysterious doorway. The Magician’s Nephew is a prequel that both deepens and complicates the original books, a kind of tour of the metaphysics, in which we learn of a nexus between worlds: not just Narnia and the real world, but dozens or hundreds of other realities, accessible via pools of water in the incredibly beguiling “wood between worlds”. What I particularly love about this multiverse is the sense that worlds have a life cycle: we see Narnia called into being, and the decaying land of Charn finally destroyed.

Abarat by Clive Barker

In some ways Abarat is another portal fantasy in the classic mode: the heroine, Candy Quackenbush, escapes from her mundane existence in Minnesota and finds her way to the fantastical archipelago of the Abarat. But the archipelago is a multiverse in itself: each island is named for one of the hours of the day (as well as more beguiling names such as “Orlando’s Cap”, “Soma Plume”, “The Isle of the Black Egg”) and each one has its own distinctive rules, peoples, creatures and myths. The islands are loosely divided by their allegiance to Day and Night but the plot and characters give way before a glorious, almost fractal level of novelty and detail as the archipelago unfolds itself to us.

There are fantasy settings which are intricately rendered alternate realities in which everything flows from first principles in an orderly fashion, and there are fantasy settings which delight in inconsistency and wild flights of invention, where the author clearly feels no compulsion to explain the setting more than is absolutely necessary. Abarat is very much in the latter category, and a hell of a lot of fun for it.

The Dark Tower series by Stephen King

Oh, The Dark Tower. Stephen King’s fantasy series deals with a legendary gunslinger who rattles through dozens of worlds, including our own, on an endless quest to reach the Dark Tower, and possibly thereby prevent the collapse of all reality. These books are all the more dear to me for being so very sprawling, flawed, nightmarish and bizarre. Should a fantasy series have an evil haunted sentient train? Should it have gun magic? A big talking bear? An apocalyptic-Western-Arthurian-science-fantasy setting? Numerology? Bird-headed people? Should the author himself appear in a cameo along with characters from many of his other books? If your answers to most of the above aren’t “obviously! of course!” then I don’t know what to say to you. Are they good books? I have no idea. The Dark Tower fascinates me. Like Abarat, it’s an epic fantasy rendered with the specialist tools of a horror writer, which might be why it largely falls into the ‘never explain, never apologise’ category of worldbuilding above. The sheer ambitious strangeness is undeniable.

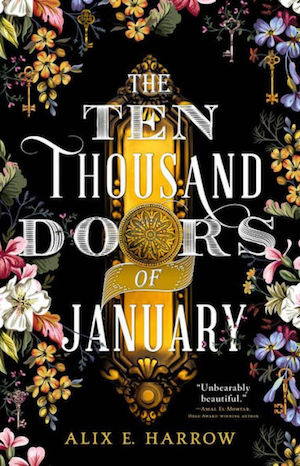

The Ten Thousand Doors of January by Alix E Harrow

The Ten Thousand Doors of January is generous in doling out all the pleasures of portal fantasy—a gorgeously rendered travelogue through a whole panoply of countries both real and imagined, full of extraordinary landscapes and artefacts, given life by Harrow’s crisp, evocative prose—but it also engages directly with the uneasy aspects of portal fantasy, interrogating the colonial implications of people from the “real world” going to sort out the problems of other places.

In this and other ways this is a novel about the latent horror of the fantasy multiverse setting. If there are ways to other worlds, those ways can be blocked and broken. The heart of the novel is the trauma of separation and isolation, which shapes every character in very different ways as they struggle to find their way back to one another, both literally and emotionally.

Originally published January 2020.

A.K. LARKWOOD studied English at St John’s College, Cambridge, and now lives in Oxford with her wife and a cat. The Unspoken Name is her debut novel.